Supporting immunisation programs in the Pacific

Whilst eHealth tools can reduce the administrative burden on nurses and doctors, when software built for high-income countries is ported across to low and middle-income countries without deep localisation, the result can be an overly complex, time-consuming burden that makes life harder and ends up being abandoned.

As we head towards the largest-scale vaccination program in history, it’s more important than ever that nations have healthcare software that is built for their context and their users. Tamanu’s immunisation module is designed for the Pacific Islands and designed to work in some of the most remote locations in the world.

A typical clinic in the Pacific Islands is very different from an Australian GP

Around 80 to 90 percent of healthcare in the Pacific Islands is delivered outside of hospitals, in local clinics. So what does a typical clinic look like?

The first and biggest difference is that there are no doctors and probably no reception or admin staff. Clinics are staffed overwhelmingly by nurses, who cover diagnosis, treatment and record-keeping. A well-resourced clinic might have a few separate consulting rooms, a shaded waiting area, and a solar-powered fridge for storing temperature-sensitive medicine. It will not have air-conditioning, although it might be raised off the ground to allow airflow underneath.

A less well-resourced clinic is more likely to be just one open space (meaning no privacy), with a dirt floor, no electricity, staffed by just one or two nurses. There are no appointments – people show up and wait in line until a nurse becomes available. A busy clinic might see 50 patients a day.

The admin burden on nurses is extraordinarily high

Typically in the Pacific Islands, patient records have been kept in huge A3 ledgers. When a patient is seen at a clinic, a nurse will enter a line in the ledger, listing the person’s name, diagnosis, treatment and the date. If the patient returns a month later, the only way to find a record of their previous visit is to manually leaf back through the book. If they return a year later, you might have dozens of books to scan through.

Nurses are incredibly time poor. They have to see a large number of patients in a limited amount of time, and anything that increases their workload is directly taking away from the time that they can devote to clinical care. At the moment, each encounter with a patient needs to be detailed in the main A3 ledger and in the patient’s individual treatment book (if they have one), and then relevant data must also be separately captured for a wide variety of public health programs, tracking diabetes, malaria and so on.

Despite the challenges, many facilities in the Pacific still do this really well. Their filing systems are excellent – impressively well-organised, clearly structured, and up-to-date. The admin burden is nevertheless onerous. In some countries, nurses have to sometimes submit more than 12 separate reports, documents or order sheets to their local Ministry of Health, on top of their own local data collection for clinical care.

Electronic records eliminate the vast majority of that two-step reporting. Our electronic medical record (EMR) software project, Tamanu, operates on a single entry model. Patient data only has to be entered once, and it is then automatically aggregated and anonymised into a country and even region-wide database, from which the Ministry of Health can produce reports on any public health matter they want to focus on, without any extra input at the clinic level.

Effective vaccination programs depend on reliable record-keeping

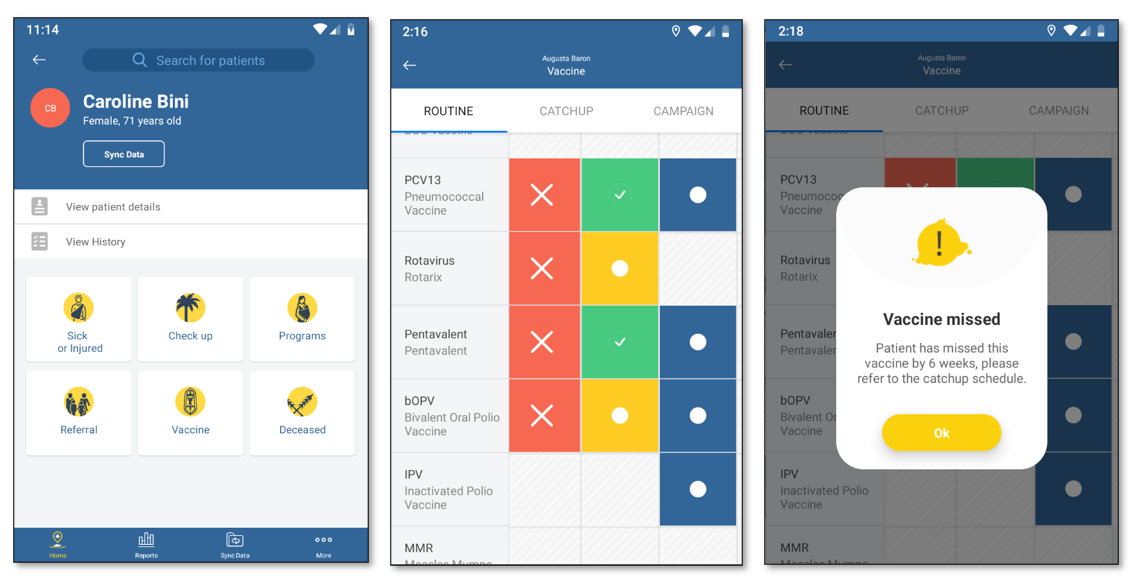

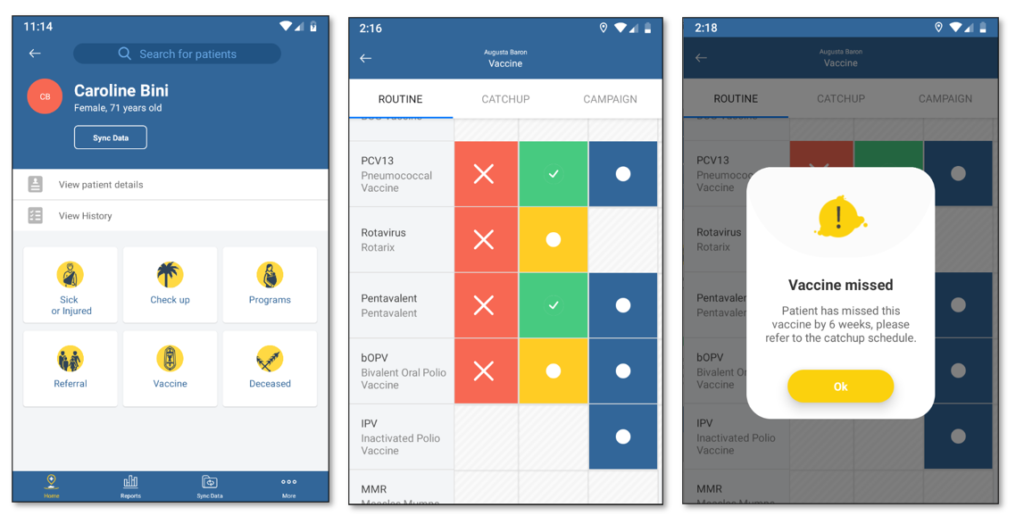

In no other setting is this data-keeping burden more onerous – and important – than in immunisation programs so we are super excited to be rolling out our new immunisation module in Tamanu across desktop and mobile.

An immunisation schedule lists out all the vaccinations a person should get over their lifespan – whooping cough at 6 weeks, MMR at 12 months, a flu jab every year, and so on. An immunisation register is a centralised database that tracks the vaccines that every individual has received and provides aggregated reporting. In addition to providing this electronic register, Tamanu’s immunisation module will provide clinical decision support to healthcare workers. When a clinician accesses a patient record, it will advise them if they are due for a vaccine, if they’ve missed one, and even flag if a clinician attempts to administer a vaccine too early or too late. This decision support reduces the cognitive burden on healthcare workers, allowing them to focus on patient care.

The module also tracks adverse reactions to vaccines, which is crucial for patient safety (for example, the current Covid-19 vaccines are not recommended for people with a history of adverse reactions to vaccines). The module works completely offline across both desktop and mobile, syncing data whenever it comes into internet range (which is critical for accessing the most isolated communities in the region and providing outreach vaccinations) and like the entire Tamanu platform, it is available free and open-source.

Our immunisation module is designed for use for routine, catch-up and campaign vaccines – these may be for COVID-19 and they may be for other programs. Over the next few months for example, Samoa will be rolling out a typhoid vaccination program. Typhoid has been endemic in Samoa since the 1960s, and can be severe. It will be important to know who has and has not been vaccinated, where there are vaccine shortages, and where vaccination drives need to be focused. People administering the vaccine will need documentation software that is simple, quick to use, responsive, and not reliant on internet connectivity. Nurses simply do not have the time or devices for complex desktop applications – that’s where Tamanu will help.

Comprehensive record-keeping gives a holistic view of a patient’s health

Diseases do not operate in isolation. For example, while typhoid fever is not usually fatal with modern treatments, people with sickle cell anaemia are at much, much higher risk of serious complications and death. Risk factors for a severe case of Covid-19 include diabetes, schizophrenia, and being on the medication prednisone – not necessarily the risk factors we might associate with a respiratory disease.

If a country such as Samoa wants to target their vaccine roll-outs to high-risk groups, they’ll be hugely assisted by a complete picture of patient health, including seemingly unrelated information such as mental illness – information which it may not occur to the individual to disclose. And it’s not just relevant to infectious disease. Non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cancer often coincide with mental disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder. Without a full picture of a patient’s situation, clinicians cannot provide the best care for patients. That’s where we intend to help because healthcare systems should support the work of nurses and doctors, not be an extra burden hanging over their heads.